This bow was built out of one of a bunch of yew branches which all came from a group of yew trees which produce some really beautiful orange heartwood. In my experience, no two yew trees produce the same quality of timber, however all of the branch staves which came from these particular trees have a good ratio of heartwood to sapwood and they all have this wonderful bright orange heartwood.

This fortunately means that none of the branch stave cut from these trees are likely to need much, if any sapwood removal in order to optimise limb composition. This is really helpful as the growth rings on these particular branches are nice and tight which is definitely what I prefer in terms of optimal yew bow wood. But tight rings on yew staves with undulating backs makes chasing a ring quite a challenge! Particularly if the stave has lots of additional character – which is kind of what I like, and is oftenwhy I chose to use a particular stave in the first place!

This particular branch stave was pretty clean across one obvious potential face, however I have to admit that the glaringly obvious deflex was not an immediately attractive quality. Fortunately the deflex was evenly distributed through both limbs and the handle section. This deflex amounted to about 3” worth so was going to require a bit of thought and consideration.

Whilst thinking about how I’d work around all this deflex, I remembered seeing a couple of beautifully made primitive osage bows made by a well know and accomplished bowyer in the US call Mike Yancey. Mike owns and runs Pine Hollow Longbows out of Arkansas. If you haven’t seen any of Mikes work, then go check out his stuff. He’s done a few really interesting podcasts and has a few youtube videos which you might find interesting. His website is here: Traditional Archery – Pine Hollow Longbows and his youtube channel is here: Pine Hollow longbows – YouTube

A couple of Mikes signature bows have quite a bit of deflex deliberately built into their design. This has always intrigued me as I’d always assumed that lots of deflex would cost a bow significant cast. Mike seems unfazed by this though and counters it to some extent by flicking the tips. But even with the tips flicked, some of his shorter bows still carry a good couple of inches of deflex overall.

Despite all that deflex, Mike and his customers report that those same bows shoot fast, hard, smooth and quietly. So with this particular branch stave already carrying a lot of natural deflex, I decided to have a go at producing a bow with a similar side profile to the shorter bows which Mike makes. That way I could encompass as much of the natural deflex into the design of this bow as possible.

My plan was to produce a medium length (56-58” N to N) flatty with an elegant pyramidal front profile. I planned to flick the tips since they were relatively knot free, and I planned to keep the last 4” of the tips static. Mike uses Osage almost exclusively so I couldn’t be sure that his basic design profile would work for our English yew. So with this in mind I opted to keep reflexing down to a minimum with a view to offsetting some of the deflex but definitely not all of it. The flicked tips would also avoid excessive stack too given that this shorter than average bow was going to get tillered to 26”

The handle section on this stave was full of beautiful orange heartwood which I wanted to maximise the potential of as a feature, so I opted to keep the handle thick enough to show off all that wood. As a result of keeping the handle so thick, the handle would obviously end up rigid. This would result in the 4” handle section plus 3” fades taking 10 inches of the bow out of action. The 4” static tips would take a further 8” out of play too. This would leave only 20” of each limb available to work. That’s not a lot of moving wood to accommodate for a full 28” draw length so I opted to keep this bow to a 26″ draw length. Since 26″ matches my own draw length, that suited me just fine! So all of that natural deflex would now act as a bit of a buffer and would mitigate the risk of building a bow that was starting to resemble quite a high stress design. Maybe that’s why Mike deliberately builds in so much deflex on his high performance short osage bows.

This particular stave was fairly easy to rough out as the grain was quite uniform for the most part. I often find that our local yew wants to tear out, even when away from knots and other typical features. I have come to think that this isn’t necessarily due to propeller twist, but is more to do with our generally higher wind speeds stressing the limbs of our local yew into growing with an uneven cross section in order to brace itself against our stronger than average prevailing winds. In fact propeller twist is something that I seldom experience with our local yew. I wish the same could be said of our white woods!!

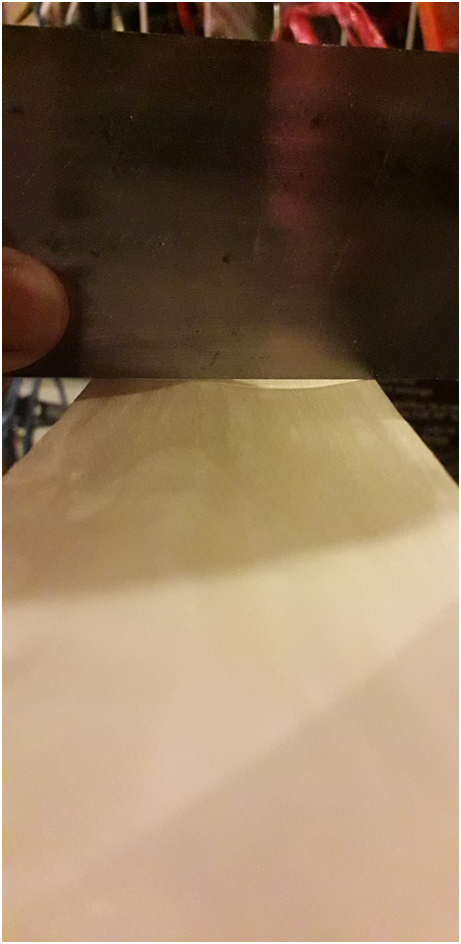

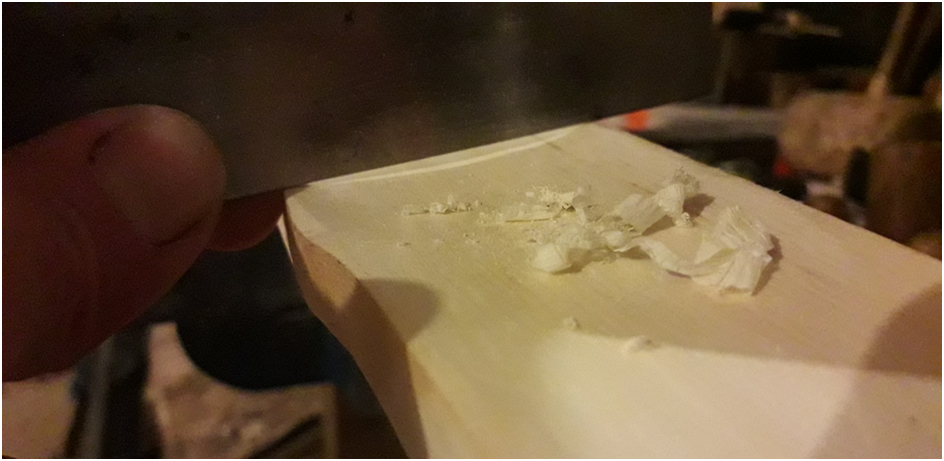

The face of this branch stave which I’d planned using as the back of the bow had previously acted as the top of this branch as it grew on the tree. As a result of this, the growth rings were tighter in this section of the limb when compared to the underside of the branch. The result of this growth is often that the pith of the branch ends up running closer to the face that acts as the top of the branch. This was the case with this particular branch. As such, the pith would need digging out of both limbs in order to optimise for limb compression strength and minimise the risk of bucked heartwood on the belly.

By the time all of the pith was out it was clear that this bow would end up incorporating a shallow hollow limb type appearance in the inner thirds of both limbs. This was just fine in my eyes as I find that a HLD cross section limb profile looks nice and enhances performance. So out came the gouge and the swan neck scrapper and soon I had both limbs free from pith and down to a nice even thickness of between 14 and 12mm distributed evenly between all the humps and bumps and twists and turns.

With the face profile and limb thickness roughed out, I got on with flicking the tips with a simple jig and some dry heat from a heat gun. I decided to keep the flicked section to a long gentle sweep rather than the usual 6” of more aggressive curve. This would allow half of the flicked section to do some work whilst keeping the last 4” completely static.

Next a small amount of dry heat was applied to the top limb fade in order to correct a small amount of string misalignment. Then it was time to cut some tillering nocks. I was quite happy with the side profile of the bow at this early point and was keen to see what the stave looked like during the first few pulls on the tiller tree. Other than an obviously stronger bottom limb, the first pulls looked nice. A bit of re balancing of the limbs to improve the elliptical tiller I wanted brought my eye back in so I could see that there were a couple of spots on both limbs which needed to be let off a bit. After that the rest of the tiller came together pretty quick.

The natural deflex and added reflex had created a shape which looked very nice once reaching full brace. Since this bow was symmetrical, I wanted to try and maintain a ¼ positive tiller throughout the tree tillering process knowing that the bottom limb on a bow this length would likely take on a fair bit of stress and a little set if shot split fingers.

Brace to 22” went smoothly but it was clear by now that a fair bit of weight removal would be necessary before pushing out to 26” as she was currently very heavy at 22”. I was aiming for a bow around 55-58 at 26” so stopped when I got to 55 at 24”. I’d shoot in the last 2” of tiller then adjust accordingly. So with the temporary nocks serving to let me shoot her in, I gave her a couple of weeks worth of stump shooting to settle in properly.

After a lot of shooting, all looked good and the positive tiller had held up well albeit reducing down to about 3/16″. It was clear by now that this design of bow was very efficient. In fact I was really impressed with the power and speed this bow was demonstrating. I shot stumps with her using some old battered 30″ 500# Gold Tip Traditional Classics which are as close to bomb proof an arrow as you’ll ever find and subsequently an excellent choice for blasting stumps with. They are also a very heavy arrow. Tipped with insert, ballistic collar and 150 grain stump heads, these things are coming in at 575 grains so I was expecting this bow to respond to them like it was being asked it to throw logs! But she was sending them on their way like my 50# Satori sends them. I was impressed!

Back at the workshop after all the shooting in the tiller still looked great and the finishing process could begin in earnest. I wasn’t intending to put this bow up for sale in my shop as this bow was intended to be a gift for a mentor of mine but I still wanted to enhance the durability of the bow’s back. So on went a couple of premium quality wild red deer rawhide strips to bomb proof her back. You can buy them here: One Matching Pair of Wild Deer Rawhide Strips – Etsy UK Then on went a couple of buffalo horn tip overlays. Last but not least, I wanted to use this bows rawhide covered back as a canvass so that the back could earn the right to sit next to all that gorgeous orange belly wood. So on went a whole King Rat Snake skin from tip to tip.

This bow had an arrow shelf cut into it to increase functionality. The shelf is cut pretty close to centre which has reduced arrow fussiness considerably. I refrained from wrapping the handle so the handle wood could shine. Covering up that gorgeous bright orange handle wood would have been criminal in my opinion!

After a very quick and easy re-tiller to account for the addition of the backings, I was ready to sand and polish her up. Then a little black and white artwork was employed along the boundary between the wood and the backing to make the contrast between front and back really pop.

To seal her up I gave her a few baths in Tung Oil to give her a wonderful satin finish which really suits yew in my opinion. Finally I built her a 12 strand B55 flemish twist string with nice small loops to keep everything in line whilst hanging onto those tiny nocks. Two Wild beaver fur silencers dampened down the tiny amount of sound that remained on this already whisper quiet bow. Fur silencers also look pretty cool and in keeping with the overall primitive theme in my opinion. You can buy them here: 1 X Pair of Beaver Fur Bow String Silencers beaver – Etsy UK

I have to say that I’m really impressed with this bow. And even though the wood that this stave provided was a major contribution to the efficiency and performance of this bow, I simply can’t help but think that this deflex reflex profile enhanced the smoothness of the draw and the retention of power which might have been lost through set born from a straight or reflexed starting point.

I’m going to continue to experiment with this profile further. I want to confirm whether or not the performance of this bow can be readily replicated in other bows of similar stature. I’m also now curious to see how bows of other woods would perform when designed this way. I will keep you posted on my findings!

Here are the stats and the photos. I hope you like her:

Mass: 566 grams

Length NTN: 56 3/4”

Width: 1 3/4” at widest

Tips: 4” static 3/8” wide at tips

Back: Marginally crowned with undulations. Face profile pyramidal.

Belly Profile: Working limb sections concaved to mirror back, transitioning at the tips to D shapes then triangular cross sections.

Tiller: Elliptical 1/8” positive.

Brace Height 5 1/2″

Draw Weight: 56lbs at 26”