This bow came from a nice clean, straight, undamaged English Elm stave which I cut back in the winter. I roughed it out green and clamped it to a slightly reflexed form to force dry it over the wood burner for a week. I then took the roughed out stave off the form and left it hanging up in the ceiling above the wood burner for a month to dry to the point of no further weight loss.

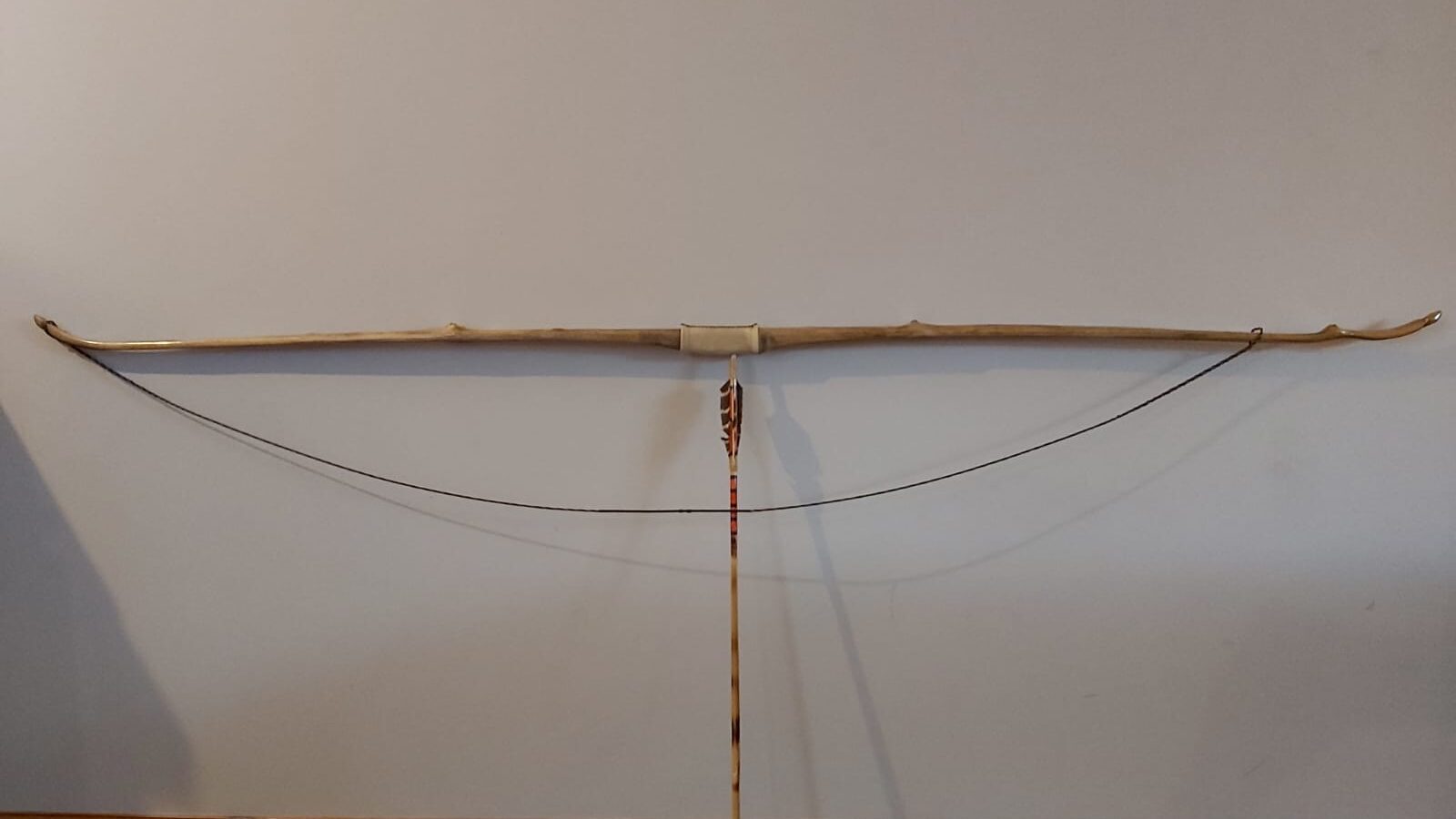

Once the stave was good and dry I chose a shape and profile (HLD pyramidal longbow with static tips) which suited the length and width of the stave (6ft X 3”). I then cleaned it up close to final dimensions and then floor tillered it. The shape looked good so I continued to tiller to brace then carried on down to 22”. I was gunning for a nice positive elliptical tiller and a final draw weight in the upper 50s as this bow was for someone who wanted a nice clean, simple, hunting weight primitive longbow.

All looked good except for a little bit of propeller twist which was making its presence known, so I opted to straighten that out whilst heat treating the slightly dug out belly. So after fixing the stave to the form again and using clamps to pull out the propeller twist I set to cooking the belly.

Half an hour with the blow torch got the belly nice and dark but without any cracks. I’ve learned over the years that properly dried whitewood staves wont check as easily when heat treated as those which are still holding 10% or more moisture. This stave was down to about 6% moisture content so I could get away with using the heavy heat application which comes with using a blow torch to heat treat the belly of a bow. Give it a try and you’ll see what I mean.

After a day to cool and reacclimatise, I checked the tiller again. The heat treating had banged on some weight and gotten rid of the propeller twist nicely. The stave was now holding about an inch and a half of reflex too. After tillering down to 26” I was getting 63ish lbs so I decided to shoot in the last 2 inches and see if the positive tiller would stick.

A few days slinging stump heads in the woods gave me chance to really shoot her in. All looked good however the tiller was now looking a bit too neutral and since this bow is symmetrical and the guy this bow is going to shoots split fingers, I opted to take some more wood off the top limb to regain that positive tiller.

With everything looking nice, I set about rawhide backing this bow to add some extra durability. As much as I love self bows, the simple reality is that one ding in the wrong place, (especially on the back and sides, or worse still back corners) and a bow could easily be compromised. I like the protection that properly made and fitted deer rawhide gives to the back of a stave bow.

I back many of the bows which are going to end up in the hands of other people as I know how rough others can be with bows. On this particular bow I opted to use some really nice thin wild red deer rawhide which I produce from deer that I’ve hunted over the winter. I process this rawhide the traditional way which ensures that it remains good and thin but incredibly strong. I sell this rawhide for a very reasonable price in my ETSY shop: Southmoorbows – Etsy UK. You can buy it here: One Matching Pair of Wild Deer Rawhide Strips – Etsy UK

After a couple of days for the titebond III and rawhide to dry thoroughly, I set about trimming the rawhide and fitting some really nice Red Deer antler tip overlay (which you can buy here: Wild English Red Deer Antler Whole Coronets 3.5 Long – Etsy UK)

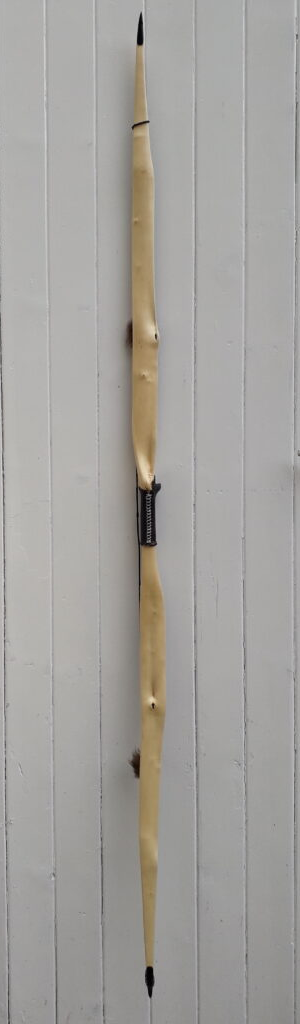

After sanding the whole bow down and polishing her up with wire wool, I stained the wood with an alcohol based black wood stain. The rawhide got treated to a coat of leather dye which once dry was wire wool scrubbed in the mid limb section to give it an aged and worn appearance.

All the final scrapping and sanding to finish brought the weigh down to 59lbs at 28”. A further few shooting in sessions saw the weight settle in to 58lb at 28”. This was about perfect.

On went a piece of my own home produced, lovely, thick wild red deer neck rawhide for a handle covering (which you can buy here: 5 X 6 Wild Red Deer Rawhide Piece 0.4 1mm Thick – Etsy UK). This rawhide handle covering got a coat of leather stain too. The handle and the bow itself were then both treated to half a dozen coats of tung oil over the next couple of weeks to seal her up good and tight.

Whilst this bow is a bit on the heavy side for me personally, the guy who received this bow loved it. It is indeed a punchy bow with no noticeable hand shock, and very quiet too. It would make a really great hunting bow.

Here are the stats and pics. Hope you like!

Mass: 678 grams

Length NTN: 67”

Width: 1 7/8” at widest

Tips: 5” static 3/8” wide

Back: Marginally crowned with minimal undulation. Face profile pyramidal.

Belly Profile: Working limb sections concaved to mirror back, transitioning at the tips to triangular cross section.

Tiller: Elliptical 1/8” positive.

Draw Weight: 58lbs at 28”